Of all the things schools could spend their money on, improving the quality of teaching through ongoing professional development of teachers can have the greatest impact on pupil outcomes. It can also be the most cost effective. So, how can we best develop teacher expertise in our ever changing educational landscape?

Forget about the notion of a teaching blueprint

If we want teachers to be highly skilled, adaptive professionals, we need to think carefully about the learning environment and resources we offer them. Too often, teachers find themselves operating in a directed profession where they are told what best practice is.

Complex methodologies and approaches to teaching and learning are reduced to simple tick box toolkit strategies designed to be mimicked without question as to their effectiveness. This was perhaps best characterised by the National Strategies’ approach to AfL and most recently by the neuromyth of learning styles which has been widely discredited by scientists, academics and prominent educationalists due to lack of evidence of any positive effect on pupil learning.

The challenge is to not only give teachers better access to the latest evidence of what has been shown to be effective, but to ensure that teachers are no longer passive receivers of the latest en vogue strategies. We need to also recognise that when best practice in teaching becomes something that's simply spoon-fed, it can potentially do more harm than good.

What could be better than best practice in teaching?

There are many who believe that we can identify what best practice is by looking at research and that central government can make decisions as to which ‘best practices’ to disseminate and dictate to teachers. But, teaching is too complex for this kind of central regulation. At the heart of good teaching sit judgement, interpretation and sensitivity, which allows good teachers to decide in real-time how best to proceed.

Better than best practice, an approach coined by Leftstein and Snell, is the sort of professional learning which seeks to develop that teacher judgement. It helps them to think about what the different options are and when best to use them, while recognising that every child, every classroom is different and will present ever changing complexities and challenges.

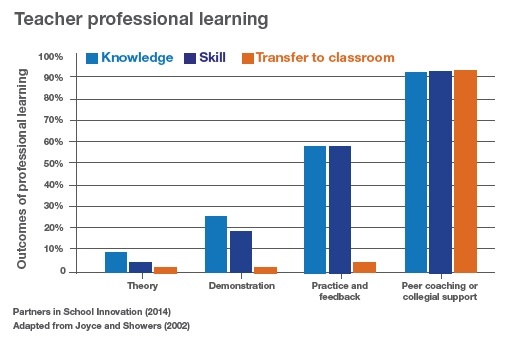

If we want an evidence based profession, we need to first and foremost look at what the evidence tells us about effective professional learning. Joyce and Showers (2002), for example, highlight the need for a blend of theory, demonstration, practice, low-risk feedback, collegial support and coaching. Kraft and Papay (2014) demonstrate that a professional atmosphere of support, trust and feedback leads to better outcomes for learners.

So, rather than focus on one size fits all best practice approaches for our classrooms, we should perhaps be looking further up stream. First and foremost, we need to consider and review best practice approaches to teacher professional learning informed by research.

Ultimately, it’s about empowering teachers by putting them in control.

Justine Greening said that she saw teacher development and school improvement as one and the same thing. But this can only be true if we allow teachers to be the drivers of change and view teaching and learning as one and the same thing.

We therefore need to focus on developing adaptive professionalism and expertise through a rich, teacher-led, collaborative approach to professional learning.

Only when we afford teachers the opportunity to connect and collaborate, can we build social capital and maximise human capital.

Only when we see teachers afforded the opportunity over time to make judgements based on other people’s research, can we build decisional capital.

Only when we invest in teachers, giving them the freedom to experiment, to fail, to engage with experts, to make refinements and find their own solutions that move the way teach forward, will we build professional capital. (Hargreaves & Fullan 2012)

If we are to truly professionalise the profession, these aspirations need to go hand in hand with developing a sense of professional efficacy. This can only be achieved by moving away from a top down directed profession where only those labelled ‘outstanding’ or similar are seen as having something to offer.

The cornerstone to teacher retention

Moreover, we may go some way to addressing the current issues around recruitment and retention. LKMco concluded in their 2015 report that: ‘if teachers are to be kept in the profession they need to feel they are having an impact. Distractions from working with pupils and constraints on their ability to act as professionals therefore hamper retention’. We know that teachers who have a strong sense of self-efficacy are more likely to:

- Have the confidence and ability to choose the best approach required for needs of their classroom

- Be resilient when faced with change

- Be secure and confident enough to engage in research and enquiry in their own classroom

- Be able to do these things collaboratively

- Want to stay in and contribute to a knowledge creating profession

Download the Shaping the Future of CPD report: "Recruit, train, develop, retain" >

Let’s not revert to a tick-box culture where we tell teachers what to do and what best practice is. If evidence and best practice are to be at the core of a school-led system, it should be a collective endeavour where we put teachers in the driving seat and trust in them to build a knowledge creating profession.

Leave a comment:

Get blog notifications

Keep up to date with our latest professional learning blogs.