On the 8th October 2021 the Education Endowment Foundation, an independent charity dedicated to breaking the link between family income and educational achievement, released the Effective PD Guidance report based on a comprehensive meta-analysis of 104 educational research papers conducted by Sims et al. Meta-analysis is increasingly being used to help the education system “see the wood for the trees”, given the mountains of (often contradictory) primary research. This approach has been used extensively by the EEF to inform their guidance papers on matters like student feedback and developing literacy. This powerful approach has now been used in service of teacher PD, which, save for a few caveats to be discussed later, is a very welcome development.

We haven't had such a comprehensive interrogation of what is arguably, the most important subject in education since the groundbreaking work of Bruce Joyce and Beverley Showers in 2002. The report is useful for schools, Trusts and Teaching School Hubs aligning their work with an evidence base and delivering better PD for their teachers. We recommend that all those involved in the delivery of PD engage in a quality audit based on these findings to refine delivery and improve outcomes. The process will also improve communication, develop best practices in procurement and improve strategic decision-making in the future.

It should also be noted that this PD meta-analysis also has important implications for those involved in the design and implementation of educational research. These considerations are discussed here.

Why is PD so important?

Why do we consider PD to be “the most important subject in education”? Well, the stakes are high. The quality of teaching is a significant factor affecting education outcomes and the research has demonstrated that it can be improved with PD. However, prioritisation isn't enough. If PD is poorly structured and lacks the key mechanisms outlined in the EEF report, students are unlikely to benefit. In our experience, this isn't just a matter of slightly worse PD leading to slightly worse outcomes. As with a rocket launch, the failure of an important system can lead to a spectacular failure to reach orbit. Space X refers to this as a “rapid, unscheduled, disassembly” (RUD).

When we first started working with schools over a decade ago, we would routinely encounter schools who had experienced a RUD of their professional learning endeavours. Poor design had led to repeated failures and frustrated school leaders had resorted to pulling yet harder on the levers of policy and monitoring to “drive change”. Teachers, in turn, had become entrenched in cynical attitudes towards “yet another initiative” and pushed back on crude monitoring. These two responses often fed upon one another, creating a toxic learning culture where no progress was possible.

It's important to acknowledge the strides made in schools since then. The last few years have seen a sea change in schools' approaches to PD. They’ve largely moved away from ineffective, summative observation. There is a broad recognition of PD as a process requiring ongoing support and skill development outside of designated INSET time, and the focus of the PD is largely evidence-informed. The EEF report is timely as it helps schools extend this evidence-informed approach from the focus of PD (instructional strategies) into the mechanics of planning and delivery, i.e. the programme itself.

By providing an evidence-informed framework for auditing PD, the report enables schools to look beyond a programme’s surface features when judging the likelihood of success. In the same way as a wise astronaut is more interested in a rocket’s engines and computers than its appearance, schools need to look beyond the headlines of “lesson study” or “instructional coaching” and attend to how these programmes expose teachers to effective learning experiences.

Discussion of findings

Since we seem to have embarked on the rocket analogy, let's struggle on with it. The EEF report encourages us to differentiate these learning experiences into groups and mechanisms. Think of “groups'' as broad systems like navigation, fuel management, propulsion and control. They support all of the vital processes which need to be coordinated for the payload to reach orbit. Nested within these systems are individual mechanisms, such as radar, fuel pumps, motors and computers which must work to support the broader systems. Said another way, groups (or systems) govern the overall potential of a PD programme to be successful and mechanisms support the extent of that success.

Click on the yellow pointers below to learn more about each system and their mechanism:

Groups and mechanisms matter

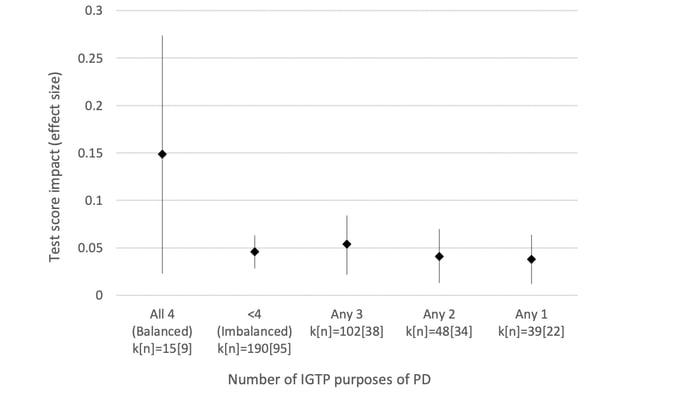

The groups (or systems) outlined by the report are: building knowledge, motivating teachers, developing techniques, and embedding practice. As you can see below, the meta-analysis found that failing to deliver to any of these systems would likely lead to unfavourable outcomes. The report refers to the notion of a “balanced design” to describe programmes which attend to each of these areas, with one or more associated mechanisms.

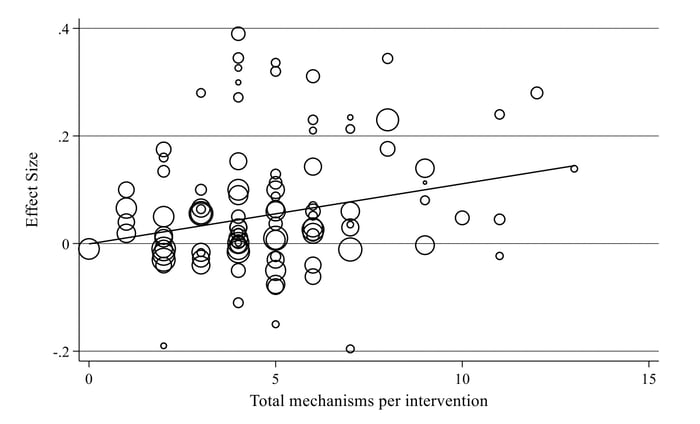

The second finding of the meta-analysis is the importance of mechanism coverage: the number of mechanisms present in the PD design.

“PD interventions incorporating zero mechanisms have an expected effect size close to zero and PD mechanisms incorporating 14 mechanisms have an expected effect size close to .17.”

Based on this tentative evidence, the authors suggest that the more mechanisms present in a programme, the greater its impact on learners. It’s interesting to note, however, in the bubble chart below, the number of high performing programmes with less than six mechanisms. Given the range in distribution, the line of best fit may not be the best way to look at this data set. If there are commonalities of mechanisms within high performing studies, this may be gently indicative that some mechanisms, or combination thereof, may be more important than others. A fruitful area of future research?

Some potential areas of confusion

There have been certain decisions in the presentation of the EEF’s guidance which could confuse readers who did not also read the underlying meta-analysis. It's most likely these decisions were made with simplicity of explanation in mind, but there’s a danger schools may draw conclusions that are not explicitly supported by the data:

- The strong sequencing of groups implied by the EEF guidance: The method of presentation used in the EEF guidance like lettering the groups ABCD implies that these learning processes must be undertaken in order. Often building knowledge does come before motivating teachers or developing practice but the importance of this sequencing wasn't tested within the meta-analysis. In fact, a different order is evident within a number of the cited studies. In particular, the MTP-S coaching program cited as an example of balanced design arguably starts with a process of guided reflection upon current classroom practice rather than an explicit process of building knowledge. The idea that sequencing can be more fluid is stated in the meta-analysis; “we acknowledge that things sometimes do not play out in this order (practice might precede new insights, for example,” but this nuance is lost in the guidance.

- The change of nomenclature between the meta-analysis and the guidance: The meta-analysis used an IGTP (Insight, Goal, Technique, Practice) framework as an organizing rationale and data collection framework; these domains were later renamed as “Groups” in the guidance. The renaming of these groups arguably subtly reframed some of the concepts in language more aligned with explicit instruction. For example, in the meta-analysis, the first step “insight” was defined as “helping a teacher gain a new evidence-informed understanding of teaching, students or themselves.” Within the guidance, this became “Building Knowledge” defined as “presenting knowledge in a way which supports understanding”

- We shouldn’t be mechanistic about mechanisms: The meta-analysis acknowledges that mechanisms can work within multiple groups, whereas the graphical representation in the guidance of mechanisms as cogs firmly rooted in a single group is too simplistic. Clearly mechanisms like “social support” and “target setting” are likely to be relevant to the process of motivating teachers, developing technique and embedding technique. Equally, accounting for cognitive load is crucial throughout the PD process and not solely applicable to building knowledge.

To summarise the concerns, the EEF report could leave school leaders with the impression that there is a firm evidence-base for adopting an explicit model of PD with all teachers. This is neither supported by the meta-analysis, nor by Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) itself. At the heart of CLT is the need to account for existing domain knowledge when making instructional decisions about matters like sequencing and scaffolding. The “expertise reversal effect” suggests experienced teachers may experience greater cognitive load in an instruction-led and highly scaffolded context when compared to a problem / practice-driven approach.

We have undoubtedly experienced this at IRIS Connect. On the whole, we find that more experienced teachers find it beneficial to engage in individualised or collective reflection prior to defining an instructional/pedagogical focus. They tend to be motivated more by informed dialogue and high levels of autonomy and internal accountability rather than highly scaffolded learning interactions. Equally, less experienced teachers tend to benefit from more structure and a tighter focus on defined pedagogical domains. All PD providers need to ensure the nature of their provision is clearly mapped to existing domain expertise or risk not meeting the needs of their most valuable assets.

Quality PD Audit, with guidance from IRIS Connect:

It was important to mention the concerns above, but none of the concerns expressed should in any way undermine the fundamental value of what has been accomplished with this work. For the first time, we have a framework of validated learning interactions against which to benchmark PD provision. With this in mind, IRIS Connect will shortly be sharing a PD auditing tool for evaluating teacher professional development, informed by the Groups and Mechanisms identified in the EEF guidance. The tool will help providers establish whether their programmes are balanced and supported by effective mechanisms. It will enable school leaders to get a holistic view of their PD by surveying staff on their learning experiences and thereby identify gaps and opportunities to improve. Crucially the tool has a Pre / Post design, allowing providers to track the impact of reform over time and gain formative feedback as their provision evolves.

To register for more information about this free PD service please click here.

Leave a comment:

Get blog notifications

Keep up to date with our latest professional learning blogs.